- Home

- Finch, Paul

Don't Read Alone Page 3

Don't Read Alone Read online

Page 3

“Just let him go,” she begged.

“We can’t let him take us to some garage.”

“Nick his motor then.”

He grabbed her by the hair, yanked her head savagely from side to side. “He’ll report it, won’t he? He’ll lead the coppers back to the Peugeot. It’s a fuck-up, for Christ’s sake! And all because of that bastard …”

He gestured in the direction they’d come from, helpless, in a fury of impotent but murderous rage. At which point Shirley saw her opportunity, reached out – and snatched the gun away from him. Andy turned abruptly, stood stock-still. The girl backed off.

“Gimme that,” he said, starting to follow her.

Shirley looked terrified, but hid the weapon behind her back. “I’m not going to let you do it.”

“Give it to me, Shirley.”

“It’s murder.”

“That didn’t bother you when I capped Forbin.”

“He was a drugs-dealer.”

“What am I then?”

“Andy, it’s not right.”

“Right? Since when do you care what’s fucking right?”

Now he was almost upon her, and Drayton could tell that he was about to strike.

“Andy, no …” she pleaded.

“You silly idiot bitch!” And he did strike, lashing out with serpent-like speed, again dealing a ferocious, flat-handed blow to her cheek: WHAP!

It echoed across the ruins.

The blow following that was quieter, but in her belly, and this one was a fist, driven with merciless force. Shirley doubled over, choking, gasping, and dropped to the grass, the gun landing beside her. Andy swept down and scooped it up, before kicking her twice, very hard, again in the guts. She rolled about in silent agony.

In the tower, the pit of Drayton’s own stomach had gone cold. He was bathed in icy sweat, his heart thumping his chest wall. He’d only stolen quick glances, but he’d seen everything. He thrust himself back out of sight to try and think – and immediately spotted his camera, which he’d placed on the windowsill as he’d watched, and which was still there, sitting out in full view. He groped towards it, but his hands were moist and shaking like leaves. Almost inevitably, instead of quietly removing the item from view, he fumbled it.

It fell noisily down the outside of the tower.

Drayton didn’t need to look to know that Andy had instantly homed in on the sound. There was a deafening silence, then: “I’ll deal with you properly later. Stay there, if you know what’s good for you.” Followed by another brutal impact.

There was no point in staying hidden now. Drayton risked one more glance, and saw the madman heading across the cloister towards his position. He backed away from the window – but where could he go to from here? His mouth tasted like bile. A frantic, helpless horror took hold of him. Jesus, where can I go? The only way out of this place was the only way in …

*

Andy didn’t know the layout of the priory ruins, yet it was easy enough to find the foot of the tower. The only problem then was how to get inside it. He stood baffled, staring at the barred-off doorway. Somehow that sissy dipshit Ralph had managed it, even though he was fourteen stone of flab. In which case, Andy could manage it too.

He examined the bars. They were cemented into the stonework rather than fitted to some kind of frame that could be opened. He grabbed two of the steel shafts and shook them angrily, testing his gigantic muscles against them – to no avail – before finally giving up and heading around the base of the tower, searching for another entrance.

*

Drayton scrambled up the remaining flight of steps, only to find that they ended in mid-air. The topmost section of the tower had long gone, and the upper rim of its encircling wall was nothing more now than weeds and jagged-edged bricks. He hurried back down to the lower window, and peered out again, sweating intensely, his heart trip-hammering inside him. Far below, Shirley lay where she’d fallen, curled in an agonised ball. But there was no sign of Andy – which suggested that he was already here, trying to get in.

Drayton didn’t want to face the reality of what this meant. But what other choice did he have?

*

Andy was a hunter by instinct. He liked to think of himself as a wolf in human guise, and as such it didn’t take him long to find the taped-off door to the dormitory, and beyond that, the door that led to the undercroft.

He paused before descending – to knock the safety-catch off, and to listen.

The underground place was dark, musty. He wasn’t frightened, but he was a professional, and professionals always took precautions. So he paused for a moment longer, and he listened all the harder.

Still there was no sound, and at last he ventured down. The grip of his Beretta was slippery with sweat, but it was the sweat of tension, nothing more. This was a nobody he was up against here; a flyspeck below the level of amateur. Compared to Terry Forbin, Andy’s former partner, into whom he’d put five bullets not two days ago, so that he could lay claim to all the cash they’d supposedly been delivering for Mr. Deakin – popping this so-called author would be easy as swiping the proverbial candy. In truth, Andy could have done it beside the road, back where the accident had occurred, but that wouldn’t have been clever – someone might have come along, and, even if they hadn’t, forensic traces would have remained, which the pigs could immediately connect with the written-off motor. No, it was better this way, off the road in a nicely secluded location.

He reached the bottom of the steps. Now that he was down there, the undercroft was dim rather than dark. But before his eyes had attuned fully, he heard the sound of feet.

He paused again, listening intently.

Then he spotted the doorway opposite, and on the other side of that, what looked like the bottom of a spiral stairway. Those feet were still approaching – it sounded as though they were actually coming down that spiral.

Shit! Andy thought, falling to a crouch, taking careful, two-handed aim.

Easy as swiping candy?

This was going to be easier even than that.

*

It was the worst descent of Drayton’s life, and that included the occasion as a kid, when bullies had coerced him into jumping off the high-dive board at the local swimming baths, and the charity parachute drop he’d made in his early-twenties after only a week’s training.

All the way down, the ivy felt as frail as paper. It repeatedly tore away from the crumbling wall, each time threatening to plunge him to his death. What was more, various horrible creatures repeatedly burst out from it, everything from sparrows to spiders, scurrying over his hands, fluttering into his face. He rarely found a proper foothold, and fell on several occasions, grabbing frenziedly at the green stuff as he plummeted five or six feet at a time. Somehow, though, it ultimately held. And when he finally reached the bottom, he slipped-swung down over the last ten feet in comical, uncoordinated fashion – like a drunken chimpanzee, he imagined – only to land on a thick cushion of springy elephant grass, which, though it knocked the wind out of him, spared him any serious injury.

Seconds later, having grabbed up the satchel, which he’d thrown down ahead of him, he was on his feet and running again, weaving his way back through the ruins. He stopped briefly beside Shirley, who had managed to get herself up into a sitting position, but who was white in the face and had blood seeping from the corner of her mouth.

“Hurry,” he urged, trying to get her to stand.

She shook her head. “Leave me … just go, while you’ve got the chance.”

“Don’t be bloody ridiculous. I can’t leave you here. He’ll kill you.”

“It’s you he wants to kill.”

“I don’t care. I’m not leaving you.”

She resisted his attempts to get her back to her feet. “You can’t help me. No-one can.”

“There’re too many girls who think that about the blokes in their life,” he retorted. Now he had her under the armpits and was forcibly lifting her. “Come on.�

��

At any moment, he expected to hear a guttural shout from behind, maybe a deafening gunshot.

“You’re wasting your time,” she groaned, though now she was upright again, albeit weakly, and allowing him to steer her back in the direction of the road.

“You tried to help me, I’m going to help you,” he said, stopping only to snatch up his keys.

“He’ll find me again.”

“Not if I’ve got anything to do with it.”

Shirley shook her head. She was still wan in the cheek, clearly nauseated by the blows she’d taken. “I know too much. He has to find me.”

“I’m not on his network,” Drayton replied, his confidence growing. Ahead, he could see the signpost and the path leading back through the hawthorn. “Come with me and you’re well away …”

And that was when they heard the shots.

There were two of them, fired in rapid succession, and though they sounded far behind, they were frighteningly loud, echoing in the lush woodland like a double-blast of thunder.

Drayton’s mouth dried as he glanced behind them. “He’s going crazy back there.”

“Leave me,” the girl moaned.

“No chance.” He continued to propel her forwards. They were now on the path. The road was just ahead. “We’re almost out of here.”

They climbed through the stile to the Sunbeam. Drayton leaned Shirley on its bodywork as he thrust his key into the passenger door and wrenched it open. The central-locking system didn’t work anymore, so after he’d eased the casualty inside, he had to hasten round to the driver’s door and unlock that one manually as well. Before climbing in himself, he glanced back once into the woods enshrouding the old priory. Nothing stirred; dense masses of heavy, silent leaf concealed everything.

Drayton swallowed, wondering what was going on back there, then jumped into the car. He switched on the ignition, gunned the engine and drove away from the verge.

Shirley still wasn’t happy. “You’re a very kind, nice man, but …”

“But what?” he asked. “But you don’t deserve someone like me? He’s got you bloody brainwashed, girl. Anyway, I’m not as kind or as nice as you may think.”

The endless reaches of trees flooded past them as they drove, though many were now lost in purple gloom. Twilight was finally infiltrating the forest.

“What’s in those bags that’s so important, anyway?” Drayton asked.

“Oh … about three-hundred grand.”

He hit the brakes instinctively. The car screeched to a halt in the middle of the road.

He looked slowly round at her. “Three-hundred …”

She nodded painfully, but now made an effort to sit upright. She was recovering her composure, if nothing else. “All unmarked bank notes. Freshly laundered.”

“Jesus God in Heaven!”

“Why else d’you think he was on the run?” she asked.

Drayton was speechless.

“I wouldn’t worry, anyway.” She dabbed the blood from the corner of her mouth with a delicate fingertip. “It’s yours now. You’ve earned it.”

“I can’t take it!”

“Why not, it’s all untraceable.”

“That’s not the point.”

She shrugged. “Dump it then.”

“Dump it?”

“Well you can hardly give it back.” She rolled a shoulder experimentally, wincing in pain. “It’s mob money. Comes from dope deals, prostitution … if you want my opinion, it’s better off with you than Andy and his like.”

Drayton wasn’t quite sure what to say. The incredible realisation slowly dawned on him that three-hundred big ones wouldn’t just solve his current financial problems, it would probably set him up for the next fifteen years; give him plenty of time to get his career off the canvas. But he couldn’t just take it – not like that. It wouldn’t be moral.

On the other hand, what else was he supposed to do with it?

Like Shirley said, it wasn’t as if he could give it back. In fact, he couldn’t even give it to the police. That would lead to questions, criminal charges, a court-case in which he’d have to give evidence – lawyers and judges again (those bastards!) – and then probably decades in some witness-protection scheme, constantly having to look over his shoulder. No bloody chance, not for him.

He put the car in gear and started driving again, this time at a more sedate pace. They’d travelled perhaps a mile before he realised that Shirley was watching him.

“I’m not kidnapping you, if that’s what you were thinking,” he said. “Soon as we hit civilisation, I’ll drop you off somewhere safe.”

“Do you beat women up, Ralph?” she asked.

He glanced at her. “What?”

“You heard.”

“Well I’m a grouchy old git, but I’ve never hit a woman. One thing about myself I’m proud of, I suppose.”

She still watched him, very closely, with those lovely blue eyes of hers.

“Like I said,” he added. “I’ll drop you off somewhere. If that’s what you want. I mean …” and now it was difficult saying exactly what he meant. “I mean, I didn’t bring you along as some kind of prize.” He tried to laugh off such a ridiculous notion.

She reached over and brushed a piece of ivy leaf from the collar of his t-shirt. “I’ll decide whether I’m your prize or not,” she said.

The laugh died on Drayton’s lips. Had she really just said that ? For a moment he had trouble keeping his attention on the road.

“Don’t look too surprised, Ralphie.” She looked back to the front. “Everyone’s entitled to a lucky day now and then.”

Drayton’s thoughts were suddenly racing so fast that he could barely contain them inside his head. Three-hundred grand sitting in the trunk, and now maybe …

“It’s a luckier day than I thought it was about ten minutes ago, I’ll tell you that,” he stammered.

“Maybe it isn’t luck. Maybe you’re being rewarded for something.”

“I can’t think what,” he was about to say, pondering his past life, his various acts of selfishness, his arguments with Sandra, his self-pitying bouts of lonely, morose drinking (mind you, all of which he’d been punished for, he reminded himself).

And then, in a flash, he thought about the ‘camouflaged man’ who’d suddenly sped across the road in front of Andy’s Peugeot, causing this whole thing to happen in the first place.

Again, Drayton almost lost his grip on the steering wheel.

Shirley had to take him by the wrist to steady him. “Just keep your eyes on the road, eh,” she said softly. “Everything’s going to be fine.”

*

In the bowels of the old priory, the full blackness of night concealed the remarkable profusion of foliage that had taken root in the centre of the undercroft.

A massed tangle of greenery, it was, growing almost to the ceiling and exploding in every direction with myriad shoots and tendrils. Of course, for all its apparent size and strength, it was essentially a delicate object, and could never last long in this lightless, underground abode. In all likelihood, when the people of English Heritage came down here sometime in the future to complete their work, they’d find little left of it but a few dried and withered fragments mingled with the trampled earth.

There’d certainly be no trace of the decomposing mass at its centre; the sagging, deflated thing from which the hungry vegetation even now was voraciously drawing its nutrients; the drained, lifeless sack, which, if the truth be told, was already scarcely recognisable for what it once had been. Though maybe, at the upper part of it, if one pushed the leaves and shoots aside and peered closely in, one might just identify a vaguely humanoid visage, though the illusion of this would quickly be dispelled – by the vines now curling en masse from its gaping maw, and the thick, fibrous stalks sprouting from the empty sockets of its eyes.

THE POPPET

The young man in the interview room was a mess: wide-eyed, white-faced and shaking. By his clo

thes and accent he was a well-heeled sort. He had a rich, resonant voice, he was articulate and educated, but the two interviewing officers were still having trouble getting anything out of him that made sense.

“You’re sure you’ve not taken something tonight?” PC Rosethorn asked.

The young man shook his head vaguely. “I don’t … I don’t touch drugs.”

“And you’ve not been drinking either?”

Again a shake of the head, though PC Rosethorn had already concluded that the prisoner was not drunk. So many were, and the stink of alcohol was usually all over them. This one just smelled of sweat; even now he was drenched, his hair a wringing-wet tangle, his t-shirt adhering to his slim torso like a second skin.

“Why on Earth did you do it?” Rosethorn asked. “You don’t seem like a bad lad.”

“I’ve told you.”

“That’s bullshit though, isn’t it? Total bullshit. Or you are on drugs. Either way, you’re lying to us.”

The young man gazed down at his clenching hands and the knots of dried blood on their knuckles. “I wish I was. I wish I was lying.”

“You’re in a lot of trouble, son,” PC Edgar, the second officer, put in.

The young man nodded. And then started to giggle. “You don’t know the half of it.” His giggle became a fluting, high-pitched laugh, which was quite unnerving. “You really don’t know the half of it.”

*

Bleaberry Beck is quaint and sleepy in that typical way of Lake District villages, but I imagine that at certain times of the year it can be a dour, oppressive place. This feeling might owe more to the eerie story that I learned on the third day of my stay there rather than to any physical factor, but, even bearing that story in mind, there is something about Bleaberry Beck’s location, which, in retrospect, seems ominous.

In appearance, it is an enchanting cluster of slate buildings – not just cottages, but pubs, craft shops and guest-houses – all centred around an ancient, ivy-clad church, in the yard of which a Celtic cross, weathered and mottled with lichen, once served as the moot-point for local men mustering to resist the armies of sheep-rustlers who frequently poured down from the Scottish borders. Its streets, exclusively of the cobbled variety, are narrow and interwoven, often leading through to small squares or quiet stable yards where there is an aura of timeless peace. The village is accessible by a single road – and a poor, unmade one at that – and sits at the extreme southern end of Lorton Vale, on a strip of land between two lakes, Buttermere and Crummock Water. It thus boasts splendid views both to the north and south. Apparently the angling is excellent, and there is pony-trekking, walking, climbing, and sailing in all the surrounding locales.

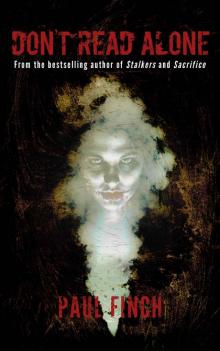

Don't Read Alone

Don't Read Alone